Browsing through the racks down at the charming Aksara bookshop recently I chanced upon a couple of interesting items. My first purchase was a handsome foldout Green Map of Jakarta which indicated some of the city's more supine places of interest and greenery. Places that take one away from the ceaseless roar of two-stroke engines and the unrelenting din of commerce. Alas, the only sizeable green areas on the map are Ragunan's large but otherwise rather drab and dilapidated zoo and the pubic topiary that surrounds Sukarno's great erection (i.e. the Monas park).

Other listed areas of greenness are almost laughable in their diminutive footprints. Menteng's Taman Suropati, for example, is often promoted as a city park whilst it in fact more closely resembles a traffic island in size. In fact let's be honest, it is a traffic island. The woeful lack of green spaces in Jakarta has been well documented of course and is brought into even sharper relief when one contrasts our megalopolitan warren of concrete rat runs with the stunning rural beauty to be found elsewhere in the Archipelago.

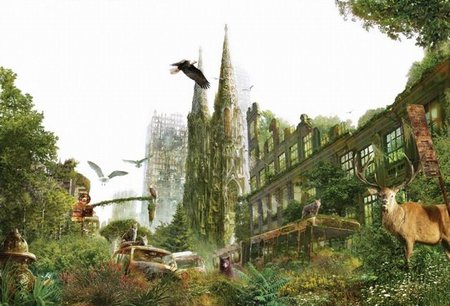

My second bookshop purchase however afforded me the opportunity to drift off into a reverie of a rather greener Jakarta, albeit a Jakarta without any actual people in it. The World Without Us by Alan Weisman is a bold thought experiment that looks scientifically at what would happen to the planet and its great cities and feats of human engineering if the entire population of the world was suddenly removed from the equation, never to return. Resembling a more analytical, non-fiction version of one of recently deceased prophet of the future JG Ballard's early disaster novels (such as The Drowned World), The World Without Us is food for thought indeed.

My second bookshop purchase however afforded me the opportunity to drift off into a reverie of a rather greener Jakarta, albeit a Jakarta without any actual people in it. The World Without Us by Alan Weisman is a bold thought experiment that looks scientifically at what would happen to the planet and its great cities and feats of human engineering if the entire population of the world was suddenly removed from the equation, never to return. Resembling a more analytical, non-fiction version of one of recently deceased prophet of the future JG Ballard's early disaster novels (such as The Drowned World), The World Without Us is food for thought indeed.I thought that I'd draw on the book this week and try and paint a picture of what would happen to the Indonesian capital over the years and millennia if its 15 million residents were to be suddenly abducted by a presumably extremely large spaceship.

Firstly, Jakarta's houses and residencies would unravel themselves after just a few short years. Indonesian housing is often of a poor quality with many seemingly being built out of breakfast cereal instead of bricks, and this would hasten its ultimate doom in the absence of any human intervention. In Indonesia's humid climate, spores would quickly penetrate the city's houses, turning hardboard to paper, rotting studs and floor joists and generally munching them to bits. Ants, roaches and even small mammals such as Jakarta's huge army of rats would soon move in and complete the job.

Moisture and rainwater would enter roofing panels around the nails, loosening their grip. Eventually, gravity will do its work, joists will cave in to the pressure and the city's roofs will collapse. An Indonesian house would probably last 20 or 30 years tops with no people around to look after it. Only bathroom tiles, the chemical property of their fired ceramic not unlike those of fossils, would remain relatively unchanged.

Meanwhile, as buildings crash down, lime from crushed concrete will raise soil pH, inviting in trees and re-greening Jakarta in a way that will make it even Ragunan Zoo look like chicken feed. The city's open sewers would jam up with plastic and other human detritus (as they pretty much do anyway now I come to think of it). Jakarta's depleted groundwater will also rise again and thus soil will be sluiced away and roads will crater.

A global warming sea level rise of an inch per decade combined with the fact that Jakarta's marshy coast is sinking (the airport toll road has allegedly sunk by over 2 meters since 1980) will ensure that most of the north of the city ends up in a watery grave. In fact 20% of Indonesia's 17,000 odd islands are set to disappear by 2050. On the other hand, the city's denuded and decimated mangroves would reappear and re-green the new coastline, wherever it ends up being.

As for Jakarta's best known icon, the previously mentioned Monas, the destabilizing ground will see even this hubristic testament to one man's pride topple and its 35 kg of lustrous golden flame become cratered before eventually disappearing. In fact, fast forwarding tens of thousands of years after our imaginary spaceship incident, the only remaining testament left to the urban sprawl that was once Jakarta will probably be the man-made, and as yet un-biodegradable, complex polymer plastics that humanity has churned out around one billion tons of since World War II.

Maybe 100,000 years hence, microbes will have evolved the enzymes needed to break down our plastic gift to the planet but until then, those Blackberry casings, Hero shopping bags and even the pen that I'm now writing this with will be the longest surviving human artifacts and the only things that remain to indicate a human presence when all other vestiges of our lives in the Indonesian capital have long since been blown to the four winds.

In this apocalyptic context, the recent Situ Gintung dam burst disaster is a metaphorically perfect embodiment of our precarious position here on this swampy floodplain. Scary stuff I know but still, look on the bright side, at least will get to go on a spaceship.